Chip shortages are rippling through sector after sector, delaying shipments of cars, game consoles and refrigerators.

Shortages in the semiconductor industry, which have already slammed automakers and consumer electronics companies, are getting even worse, complicating the global economy’s recovery from the coronavirus pandemic.

Chip lead times, the gap between ordering a chip and taking delivery, increased to 17 weeks in April, indicating users are getting more desperate to secure supply, according to research by Susquehanna Financial Group. That is the longest wait since the firm began tracking the data in 2017, in what it describes as the “danger zone.”

- Nearly 28 tons of cocaine seized after police access encrypted network

- UK jobless rate falls as workers drop out of labour force

“All major product categories up considerably,” Susquehanna analyst Chris Rolland wrote in a note Tuesday, citing power management and analog chip lead times among others. “These were some of the largest increases since we started tracking the data.”

Chip shortages are rippling through industry after industry, preventing companies from shipping products from cars to game consoles and refrigerators. Automakers are now expected to lose out on $110 billion in sales this year, as Ford Motor Co., General Motors Co. and others have to idle factories for lack of essential components. That’s undercutting economic growth and employment, as well as raising fears of panic ordering that may lead to distortions in the future.

The chip industry and its customers watch lead times as an indicator of the balance between supply and demand. A lengthening of the gap indicates that buyers of semiconductors are more willing to commit to future supply to avoid a recurrence of shortfalls. Analysts track these numbers as a harbinger of hoarding that can lead to the accumulation of too much inventory and sudden declines in orders.

“Elevated lead times often compel ‘bad behavior’ at customers, including inventory accumulation, safety stock building and double ordering,” Rolland wrote. “These trends may have spurred a semiconductor industry in the early stages of over-shipment above true customer demand.”

The situation has been complicated by a resurgence of coronavirus cases in Taiwan, a key location for chip manufacturing. The country has closed schools, curbed social gatherings, and shut museums and public facilities. While businesses and factories are operating, the government may have to consider broader restrictions.

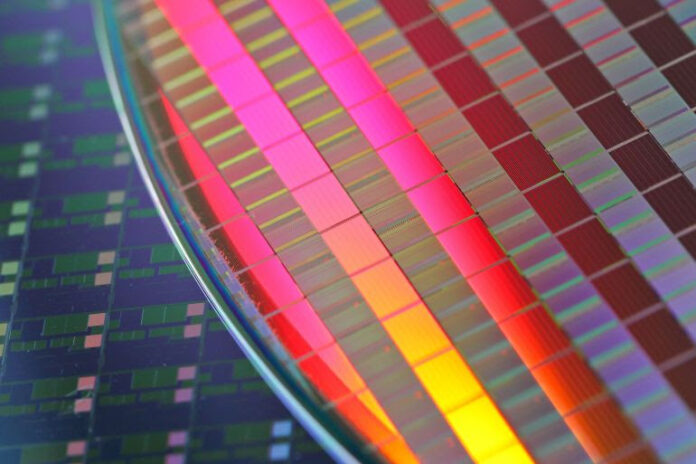

The country is home to Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., which is the world’s most advanced chipmaker and counts Apple Inc. and Qualcomm Inc. among its many customers. Local manufacturers also produce less glamorous — but equally critical — chips, such as display driver ICs that have been a particularly painful bottleneck for global production.

On Wednesday, Taiwan’s Centers for Disease Control raised the island-wide alert level, extending Covid-containment measures to the whole country. The same day, the Water Resources Agency said Taiwan needs to tighten water-saving measures because little rain has fallen during the traditional rainy season, aggravating a drought that has also threatened production.

TSMC said in a statement that it will continue to tighten its water usage and does not anticipate the measures will affect its operations.

In his report, Rolland wrote that the current wait level of 17 weeks climbed from the 16-week level and marks a fourth consecutive month of “sizable” expansion.

Lead times for certain products are increasing sharply, even after months of shortages. Power management chips, for example, spiked to 23.7 weeks in April, a wait time about four weeks longer than a month earlier, according to Susquehanna. Industrial microcontrollers order lead times extended by three weeks, some of the steepest increases Rolland has seen since he began tracking the numbers in 2017, he wrote.

Delays are often worse for smaller manufacturers, with headphone makers facing lead times longer than 52 weeks, according to people familiar with the supply chain. This has forced companies to redesign products, shift priorities and, in at least one case, completely abandon a project, said one of the people, asking not to be named because the information is not public.

About 70% of the companies that Rolland tracks have expanding lead times, compared with 20% that have seen lead times contract. NXP Semiconductors NV, a major auto chip supplier, has lead times of more than 22 weeks now, up from around 12 weeks late last year. STMicroelectronics NV, another key auto chip supplier, saw lead times rise by more than four weeks in April to more than 28 weeks.

Such outsized increases may reflect over-ordering by some customers, who could be concerned about the impact of shortages on their businesses. Historically, companies have been able to cancel chip orders without penalty, although that has begun to change.

“Beginning with January data, we have witnessed numerous large JUMPS in reported LTs,” Rolland wrote, referring to lead times. “Whereas in prior years, an individual company would typically move their stated LTs up and down just a few days in a given month, starting this year we have seen significant jumps in LTs that have skewed our data.”