Tutu, who was 90 years old at the time of his death, died in Cape Town on Sunday.

Linda Malinda, now 63, recalls her father telling her, “Go to school, you must fight for your rights knowing exactly what you are fighting for.” She still lives in the same house she shared with her parents in the 1970s, just a few meters from the anti-apartheid icon’s home in the township, which served as a battleground in the campaign against a ruthless minority dictatorship. In 1985, the world’s most famous clergyman was consecrated as Johannesburg’s first black Anglican bishop. The schoolteacher had walked out of the classroom twenty years before to protest the worsening educational standards for black students and the implementation of racial segregation in schools.

- Damon Galgut: the Booker-winning star of modern African literature

- Al Unser, four-time Indy 500 winner, dies at 82

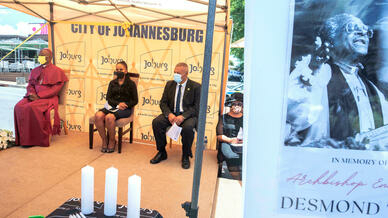

Tutu remarked in 1995, “They made care to teach them just enough English for them to understand the commands they will be given.” A few dozen people, some clad in black-and-white church uniforms, gathered for a religious ritual in front of Tutu’s residence, along the popular Vilakazi Boulevard, on a hot summer day in the southern hemisphere. A blue plaque on the wall of Tutu’s house tells visitors that the building had belonged to a “champion of human rights.” On the dusty street where two liberation struggle luminaries and Nobel laureates — Tutu and Nelson Mandela — previously resided just a few dozen metres apart, a tiny stage and speakers have been erected up.

The “Nobel Prize Walk” is indicated with a sign. Tourists in large groups come to see what is going on. “Thank you for all you have done for mankind” and “Thank you for being the voice of the voiceless,” several wrote in a condolence book on a table, the pages softly flipped by the breeze. Senior church leaders arrive minutes before the event begins, quickly exiting their luxury limousines and hurriedly donning their robes on the sidewalk. The first choir to perform the opening performance were members of the top-ranked Premier Soccer League side Orlando Pirates, who were clad in black tracksuits. During the fatal June 1976 Soweto riots, Tutu criticized police assault against children from the pulpit. Gradually, he became the “voiceless” Mandela, who was imprisoned and constantly threatened by apartheid security agents.

“We would get up early on Sundays to go to church. And we knew he would be presiding every time we saw…the large army cars “Mathabo Dlwathi, 47, expressed his dissatisfaction with the situation. “We knew they wanted to murder him,” she said, “but for some inexplicable reason they never got the chance.”

Reverend Xolani Dlwathi, a dean at the Johannesburg church, remarked, “There was just some sanctity about him.” Various segments of society, including Johannesburg’s recently elected mayor, Mpho Phalatse, paid homage to the revered anti-apartheid crusader. “I wish that, like the Archbishop, we will have the courage to face our reality,” she remarked.